The prosecution of Wikileaks founder Julian Assange will serve as a watershed precedent for internet censorship, as the United States Government is faced with an opportunity to disincentive any copycat attempts to disclose national security secrets. Counterintelligence protocols meant to limit the damage caused by improper disclosure of such information failed in numerous cases relating to Wikileaks. The alleged collaboration with GRU intelligence asset Guccifer 2.0 during the 2016 DCLeaks.com operation is reasonably suspicious, so the prosecution will seek to discourage individuals around the world from leaking classified information to the general public by making Assange an enemy of the Republic– drawing causal inferences meant to illustrate how the leaks have been weaponized by foreign intelligence adversaries.

While illegality of action in deed may be punished by warranted authorities, the American government does not have much legal authority applying American laws abroad. For example, there are significant hinderances to forcibly shutting down the internet infrastructure used to maintain the domain meaning it is not possible to sue the Swedish servers that maintain the public facing Wikileaks website.

Instead, the United States Government will attempt to prosecute the Australian national by applying at least ten identifiable federal crimes, the most compelling that Assange has engaged in a conspiracy by encouraging American security clearance holders to betray their legal obligations, enticing them to improperly disclose American national defense information. There is an interesting subtextual debate within the belief expressed by Assange that the term ‘classified’ is not a legal term, because in the event of his extradition to the United States his indigence to the law may affect the legal defense Assange is able to receive.

War Logs Debate

There exists a juxtaposition of some documents which are relevant and worthy of disclosure with others that seem targeted for disclosure deliberately to diminish the dynamic advantage held by the American intelligence agencies or to violate the letter of the law. While the United States government should prosecute individuals responsible for making such information available to all interested parties; citizens of our country and potential foreign threats, there are tangible virtues for allowing the American public to maintain access to many of the controversial leaked documents.

The freedom to criticize government officials and policies lies at the very heart of a democracy, and the degree to which a society tolerates the suppression of such criticism is a certain measure of its pulse

Friedman, Robert “Freedom Of The Press: How Far Can They Go?”

A well-informed society will be no less safe from the disclosure of pertinent information, when the secrecy of that information serves only to entrench private political interests at the expense of empowering the collective judgement of our nation’s brightest minds to consider the situations in which we are threatened as a society. Over-classification of pertinent information could lead us all to lose members of our communities in wartime service when secret rationales for decisions are kept from public debate. While the Federal government preserves the tenet of freedom of speech as defined by the Bill of Rights, the Supreme Court of the United States has reserved significant discretion for provisions meant to protect “national defense information” from being mistreated.

Some disclosures made by Wikileaks were considerably worthy of publication in that they reveal decisions that have had global ramifications, while others had little relevance to an informed public debate. The disclosure of some components of the Afghan war logs are arguably worthy of public debate, in that the war on terrorism should have been more deeply understood by those American citizens asked to die in service to the cause. Furthermore, Assange’s investigative hackivism as it relates to allegations of child trafficking are on the surface noble. On a more controversial boundary, the example below demonstrating the capabilities of corporate solutions which may violate the expectation of privacy is arguably a meritorious report insofar as the government should be punished for allowing richer civilians to exploit those who could not afford services in this video without fear of prosecution.

Public interest?

Julian Assange’s main defense is that he works on behalf of the public interest by revealing secrets, yet this is not recognized as a feasible mitigating argument to diminish the weight of his crimes. The articulated defense stands either ignorant of the rights afforded to the client and possibly completely indigent to the American legal definition of national defense information, which may force Assange to waive the rights afforded by venue such as the ability to obtain Brady material evidence.

George W. Croner, “The Assange case shows that a “public interest” defense to unauthorized disclosures of classified information is neither wise nor workable,” University of Pennsylvania Center for Ethics and the Rule of Law

Consider further that highly classified information describing this collection program and the intelligence sources and methods used in its execution are leaked to a journalist. While the leak and its subsequent reporting are likely to be inaccurate in certain respects, the reporting is sufficient to prompt the foreign target to take countermeasures that compromise the collection activity and seriously reduce the intelligence acquired. After investigation, the FBI successfully identifies the leaker who is indicted under provisions of the Espionage Act, including 18 U.S.C. § 798. Under the construct advanced by proponents of a “public interest” or “public accountability” defense, this defendant would be entitled to assert an affirmative defense that compels the government to make significant public disclosures which reveal additional sensitive aspects of the program. These matters are widely reported since the trial is covered by both print and broadcast media. As collateral damage, the widespread reporting of the disclosures the government is required to make at trial to prove its case prompts another foreign government to institute countermeasures that neutralize similar collection activities, unknown to the leaker, directed at its communications. Additional critical foreign intelligence information unavailable from any other source is lost.

Major Incidents

The criminal archive maintained by Wikileaks is not entirely managed by Julian Assange alone, but the superseding indictment filed in 2019 included 18 specific charges stemming from three major conspiratorial elements. The leaks vary in the ways they damage the fundamentally advantageous position of the United States intelligence community, but the attempted cyber intrusion charges will likely stem into four main prosecutorial avenues and then there will be less severe charges which can rack up the prison sentence for public fright.

Count 1: 18 U.S.C. § 793(g)

Conspiracy To Receive National Defense Information

To embolden potential recruits, ASSANGE told the audience that, unless they were “a serving member of the United States military,” they would have no legal liability for stealing classified information and giving it to WikiLeaks because “TOP SECRET” meant nothing as a matter of law.

To obtain documents, writings, and notes connected with the national defense; and with reason to believe that the information was to be used to the injury of the United States and the advantage of any foreign nation; To willfully communicate documents relating to the national defense; from persons having lawful possession of or access to such documents, to persons not entitled to receive them;To willfully communicate documents relating to the national defense from persons in unauthorized possession of such documents to persons not entitled to receive them, In furtherance of the conspiracy, and to accomplish its objects, ASSANGE and his conspirators committed lawful and unlawful overt acts, including but not limited to, those described in the … Superseding Indictment.

Counts 2-4: 18 U.S.C. § 793(b) and 2

Obtaining National Defense Information

Counts 5-8: 18 U.S.C. § 793(c) and 2

Obtaining National Defense Information

Counts 9-11: 18 U.S.C. § 793(d) and 2

Disclosure of National Defense Information

Counts 12-14: 18 U.S.C. § 793(e) and 2

Disclosure of National Defense Information

Counts 15-17: 18 U.S.C. § 793(e)

Disclosure of National Defense Information

Count 18: 18 U.S.C. §§ 371 and 1030

Conspiracy To Commit Computer Intrusion

When the Book is Thrown

Title 18 U.S.C. § 793: Whoever, for the purpose aforesaid, receives or obtains or agrees or attempts to receive or obtain … anything connected with the national defense, knowing or having reason to believe, at the time he receives or obtains, or agrees or attempts to receive or obtain it, that it has been or will be obtained, taken, made, or disposed of by any person contrary to the provisions of this chapter; or Whoever having unauthorized possession of, access to, or control over any document, writing, code book, signal book, sketch, photograph, photographic negative, blueprint, plan, map, model, instrument, appliance, or note relating to the national defense, or information relating to the national defense which information the possessor has reason to believe could be used to the injury of the United States or to the advantage of any foreign nation, willfully communicates, delivers, transmits or causes to be communicated, delivered, or transmitted, or attempts to communicate, deliver, transmit or cause to be communicated, delivered, or transmitted the same to any person not entitled to receive it, or willfully retains the same and fails to deliver it to the officer or employee of the United States entitled to receive it; Conspiracy Angle: (g) If two or more persons conspire to violate any of the foregoing provisions of this section, and one or more of such persons do any act to effect the object of the conspiracy, each of the parties to such conspiracy shall be subject to the punishment provided for the offense which is the object of such conspiracy.

Title 18 U.S.C. § 794: Whoever, with intent or reason to believe that it is to be used to the injury of the United States or to the advantage of a foreign nation, communicates, delivers, or transmits, or attempts to communicate, deliver, or transmit, to any foreign government, or to any faction or party or military or naval force within a foreign country, whether recognized or unrecognized by the United States, or to any representative, officer, agent, employee, subject, or citizen thereof, either directly or indirectly, any … information relating to the national defense, shall be punished by death or by imprisonment for any term of years or for life, except that the sentence of death shall not be imposed unless the jury or, if there is no jury, the court, further finds that the offense resulted in the identification by a foreign power (as defined in section 101(a) of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978) of an individual acting as an agent of the United States and consequently in the death of that individual, or directly concerned nuclear weaponry, military spacecraft or satellites, early warning systems, or other means of defense or retaliation against large-scale attack; war plans; communications intelligence or cryptographic information; or any other major weapons system or major element of defense strategy. Conspiracy Angle: (c) If two or more persons conspire to violate this section, and one or more of such persons do any act to effect the object of the conspiracy, each of the parties to such conspiracy shall be subject to the punishment provided for the offense which is the object of such conspiracy.

Title 18 U.S.C. § 798: Whoever knowingly and willfully communicates, furnishes, transmits, or otherwise makes available to an unauthorized person, or publishes, or uses in any manner prejudicial to the safety or interest of the United States or for the benefit of any foreign government to the detriment of the United States any classified information—concerning the nature, preparation, or use of any code, cipher, or cryptographic system of the United States or any foreign government; or concerning the design, construction, use, maintenance, or repair of any device, apparatus, or appliance used or prepared or planned for use by the United States or any foreign government for cryptographic or communication intelligence purposes; or concerning the communication intelligence activities of the United States or any foreign government; or obtained by the processes of communication intelligence from the communications of any foreign government, knowing the same to have been obtained by such processes—Shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than ten years, or both.

Title 50 U.S.C. § 783: It shall be unlawful for any officer or employee of the United States or of any department or agency thereof, or of any corporation the stock of which is owned in whole or in major part by the United States or any department or agency thereof, to communicate in any manner or by any means, to any other person whom such officer or employee knows or has reason to believe to be an agent or representative of any foreign government, any information of a kind which shall have been classified by the President (or by the head of any such department, agency, or corporation with the approval of the President) as affecting the security of the United States, knowing or having reason to know that such information has been so classified, unless such officer or employee shall have been specifically authorized by the President, or by the head of the department, agency, or corporation by which this officer or employee is employed, to make such disclosure of such information. It shall be unlawful for any agent or representative of any foreign government knowingly to obtain or receive, or attempt to obtain or receive, directly or indirectly, …. any information of a kind which shall have been classified by the President (or by the head of any such department, agency, or corporation with the approval of the Presiden as affecting the security of the United States, unless special authorization for such communication shall first have been obtained from the head of the department, agency, or corporation having custody of or control over such information. Any person who violates any provision of this section shall, upon conviction thereof, be punished by a fine of not more than $10,000, or imprisonment for not more than ten years, or by both such fine and such imprisonment, and shall, moreover, be thereafter ineligible to hold any office, or place of honor, profit, or trust created by the Constitution or laws of the United States.

Other commonly used statutes include:

18 U.S.C. § 952: punishes employees of the U.S. who, without authorization, willfully publish or furnish to another any official diplomatic code or material prepared in such a code, or coded materials in transmission between a foreign government and a U.S. diplomatic mission, with a fine and/or a prison sentence of up to 10 years.

Very clearly, the Wikileaks Cablegate collection directly contravenes this law. Cablegate is what Wikileaks calls the Public Library of US Diplomacy; the supposed largest public archive of American diplomatic history existing in the public sphere. These official diplomatic transmissions were the direct object of the publishing effort; obviously made without authorization by the United States Government.

18 U.S.C. § 1030(a)(1): punishes the willful retention, communication, or transmission of classified information retrieved by means of knowingly accessing a computer without (or in excess of) authorization, with reason to believe that such information could be used to injure the U.S. or aid a foreign government. This provision also imposes a fine and/or imprisonment for not more than 10 years.

Conspiracy To Commit Computer Intrusions

A. To knowingly access a computer, without authorization and exceeding authorized access, to obtain information that has been determined by the United States Government pursuant to an Executive order and statute to require protection against unauthorized disclosure for reasons of national defense and foreign relations, and to willfully communicate, deliver, transmit, and cause to be communicated, delivered, or transmitted the same, to persons not entitled to receive it, and willfully retain the same and fail to deliver it to the officer or employee entitled to receive itB. To intentionally access a computer, without authorization and exceeding authorized access, and thereby obtain information from a department and agency of the United States and from protected computers;in violation of the laws of the United States and of any State, and to obtain information that exceeded $5,000 in value,

C. To knowingly cause the transmission of a program, information, code, or command, and as a result of such conduct, intentionally cause damage without authorization to protected computers

D. To intentionally access protected computers without authorization, and as a result of such conduct, recklessly cause damage

E. In furtherance of the conspiracy

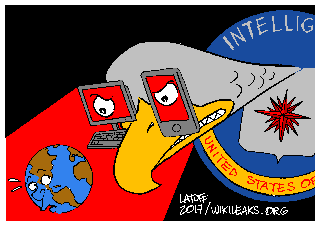

Since the filing of the superseding indictment, the United States Government prosecuted Joshua Schulte, a former NSA and CIA employee, for leaking the suite of cyber espionage tools known collectively as Vault 7. In the frame of an insider threat driven to action by Assange’s conspiratorial efforts to release classified documents onto the internet, Schulte dramatically endangered the technological superiority of the United States.

United States v. Progressive, Inc.

the question before this Court involves a clash between allegedly vital security interests of the United States and the competing constitutional doctrine against prior restraint in publication. The government argues that its national security interest also permits it to impress classification and censorship upon information originating in the public domain, if when drawn together, synthesized and collated, such information acquires the character of presenting immediate, direct and irreparable harm to the interests of the United States.

467 F. Supp. 990 (W.D. Wis. 1979)

18 U.S.C. § 1924: prohibits the unauthorized removal of classified material. It applies to government officers or employees who “knowingly take material classified pursuant to government regulations with the intent of retaining the materials at an unauthorized location,” and it imposes a fine of up to $1,000 and a prison term of up to 1 year.

In Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697, 51 S. Ct. 625, 75 L. Ed. 1357 (1931), the Supreme Court specifically recognized an extremely narrow area, involving national security, in which interference with First Amendment rights might be tolerated and a prior restraint on publication might be appropriate. The Court stated: ‘The Court is convinced that the government has a right to classify certain sensitive documents to protect its national security. The problem is with the scope of the classification system.’

Near v. Minnesota (1931)

Since Assange is not a government official nor an employee, this would be charged only because of the provisions put forth in the Espionage Act “If two or more persons conspire to violate this section, and one or more of such persons do any act to effect the object of the conspiracy, each of the parties to such conspiracy shall be subject to the punishment provided for the offense which is the object of such conspiracy.” As such, when Americans are charged for collaborating with Wikileaks these may be extended to have been stimulated by the conspiracy.

18 U.S.C. § 641: punishes the theft or conversion of government property or records for one’s own use or the use of another. It does not explicitly prohibit disclosure of classified information, yet it has been used in such cases. Violators may be fined and/or imprisoned for not more than 10 years.

Julian Assange’s Wikileaks website solicits funding from international supporters, which may constitute as using record’s for one’s own use considering his revenue is dependent upon the further maintenance of a treasure trove of secret documents.

42 U.S.C. § 2274: punishes the unauthorized communication by anyone of “Restricted Data”, that is, data dealing with nuclear weapons or systems, or an attempt or conspiracy to communicate such data. If done with the intent of injuring the U.S., or in order to secure an advantage to a foreign nation, it calls for a fine of not more than $500,000 and/or a maximum sentence of life in prison. Other provisions punish with lesser sentences attempts or conspiracies to disclose such data.

50 U.S.C. § 421: protects information concerning the identity of covert intelligence agents. Intentional disclosure, learning the identity through exposure to classified information and revealing it, or learning the identity through a “pattern of activities intended to identify and expose covert agents” is subject to prison sentences of varying lengths from 3 to 10 years, and to fines. “To be convicted, a violator must have knowledge that the information identifies a covert agent whose identity the U.S. is taking affirmative measures to conceal. An agent is not punishable under this provision for revealing his or her own identity, and it is a defense to prosecution if the United States has already publicly disclosed the identity of the agent”

To highlight just how severely the Wikileaks organization violated this specific legal statute, the Intelligence Identities Protection Act, consider just one example of political reporting from a Central Asian nation. While Tashkent is not one of the most compelling city for American politicos, the Wikileaks public diplomacy effort is a prime example of deliberately exposing classified information sources in a way that significantly endangered the life of our sources.

(C) Summary: Although his face was covered in bruises, the physical resemblance to the President is striking. In a wide-ranging conversation with poloff, Islom Karimov’s estranged nephew, Jamshid Karimov, and Jamshid’s mother, Muslima Karimova — the President’s sister-in-law — revealed details about their famous relative. They said that President Karimov was never an orphan, as his official biography asserts, but grew up in a “normal family.” Threatened politically by a minor corruption scandal involving his older brother, Hurshid, Karimov began to distance himself from his family in the mid-eighties; he broke off contact entirely when he became First Secretary of the Uzbek SSR in 1989. The Jizzak Hokimiyat maintains Jamshid and his mother in modest comfort — perks given in exchange for keeping a low profile. Jamshid, a small-time journalist with casual connections to the local human rights community, claimed that his recent decision to sign on as a stringer with IWPR prompted local authorities to have him beaten. Jamshid’s IWPR colleague, however, said that the beating was more likely a random act of violence. End summary.

Deliberate disclosure of strictly protected diplomatic sources

NEVER AN ORPHAN ————— 2. (C) On December 26, poloff spoke withJamshid Karimov(strictly protect), a Jizzak-area journalist hired in October as a stringer by the USG-funded media NGO, Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR). As reported in a short Reuters news bulletin,Karimovhad been beaten by two unidentified assailants on December 20. The article mentioned that Karimov is the nephew of President Islom Karimov. Poloff was greeted at the family’s small apartment by Jamshid who, even with a bruised face, closely resembles his uncle, and by Jamshid’s mother,Muslima Karimova(strictly protect), the widow of President Karimov’s elder brother Arslan. Over the next hour and a half, Jamshid and Muslima discussed their family’s break with Uzbekistan’s First Family, providing tantalizing glimpses into the President’s early career and family life.

Works Cited

1. Friedman, Robert “Freedom Of The Press: How Far Can They Go?”

3. 307_GAMMA-201110-FinFly_LAN, Video